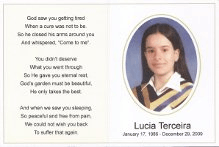

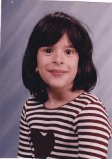

Lucy Terceira

Toronto, Ontario

“My beautiful sister Lucy passed away in December of 2009. I cannot express accurately what the passing of my sister has done to our family. To say that it has been devastating would be an understatement. It was devastating enough to get the Lafora diagnosis several years ago, and then to lose her was and still is unbearable.

We are from Toronto, Ontario. My sister passed away just a few weeks shy of what would have been her 24th Birthday. Her battle with Lafora went on for approximately 10 years. Lucy was a super bright energetic teenager and at the age of 14 we knew that something was wrong. Her balance was off, she started dropping things, complained of headaches and her vision and loss of power on her ankles and legs when walking, then the seizures started. We saw a few neurologists and several other medical professionals and everyone diagnosed epilepsy. We knew it was much more than that. Medication was simply not controlling the seizures and trial and error went on for a while until we found a balance. When we were introduced to Dr. Minnassian several years ago it only took about 4-6 weeks to get the diagnosis we were not prepared for.

This disease is monstrous. Within a few short years, my sister’s energetic body became so frail and dependant. I still cannot believe how the disease progressed. My sister towards the end could not walk, said a few words here and there, and had a G-tube, but boy could she ever still smile!!! 🙂 In the end, my sister lost her battle with Lafora because of complications with her G-Tube. After going in to the hospital to have it replaced somewhere along the process her stomach was ruptured. Later on that day, when my sister’s discomfort did not pass with some medication per the radiologist’s order, we brought her back in to the hospital. Within that last hour, we knew something was very wrong. She was slipping away from us. Her vitals were almost non-existent. Things happened so quickly. She was put on life support that night and on the following morning they operated to mend her stomach. We were in shock! They told us she might not make it through the operation. She did though, my sister was a fighter! For a few weeks after that although she was still critical because of all of the infections she got, we never lost hope. When my sister was at her weakest, Lafora kicked in overdrive. Her seizures did not subside. The only way to give her body any sort of rest was to sedate her. She was sedated for long periods of time. It was so heart breaking. We knew we would lose her to Lafora because a cure was not yet had, but not because of her G-tube. I am still having a hard time with this as I type these words. The emotions are so uncontrollable right now. The tears are dropping steadily on my keyboard.

My sister passed away peacefully with us loved ones at her side, so that makes the grieving a bit easier. Throughout her stay at the hospital, Dr. Minassian was always within reach, God bless him. He even came to visit with my mom and sister. We donated my sister’s brain, heart and muscle to help with research as the Gellel family did several years ago with their daughter Diane. We keep telling ourselves now that it is selfish to want my sister alive and back with us, because she was not like you and I, she was ill. Her beautiful smiling face only went so far. She was confined to a wheelchair, ate through a tube, could barely speak and needed a lot of suctioning towards the end of her fight. It hurt like hell to see what she went from being to what the disease did to her over the years. Her beautiful face remained though, and her smile was as radiant as always. God only takes the best. we will never forget this.

To all of you who have lost someone to this disease, we share in your grief immensely. We personally know Sam and Rita Gellel who have lost two of their daughters to Lafora. The level of grief is so difficult to fathom. Keep strong everyone and hold your children and family members a little tighter each time.”

Biography

My sister Lucy was diagnosed with Lafora several years ago. Lucy was an energetic teenager and actively involved in martial arts up until the age of 16, when we knew something was very wrong with her. It began with the breaking of dishes and Lucy spilling her drinks. Next, Lucy was always tripping and losing her balance. All of our family doctors told us that nothing was wrong and that this stage would pass. Then, shortly after her 16th Birthday, Lucy fell down the stairs, a result of having a seizure. Shortly after that Lucy was put on a series of medications, all of which were not affectively controlling her seizures. Her neurologist at the time recommended that we pay Dr. Minnassian a visit. A few months afterwards, we were given the terrible news that Lucy had been diagnosed with Lafora.

My sister Lucy was diagnosed with Lafora several years ago. Lucy was an energetic teenager and actively involved in martial arts up until the age of 16, when we knew something was very wrong with her. It began with the breaking of dishes and Lucy spilling her drinks. Next, Lucy was always tripping and losing her balance. All of our family doctors told us that nothing was wrong and that this stage would pass. Then, shortly after her 16th Birthday, Lucy fell down the stairs, a result of having a seizure. Shortly after that Lucy was put on a series of medications, all of which were not affectively controlling her seizures. Her neurologist at the time recommended that we pay Dr. Minnassian a visit. A few months afterwards, we were given the terrible news that Lucy had been diagnosed with Lafora.

Several times within the last few years, we thought that we were going to lose Lucy. This disease is absolutely and 100% completely heart breaking. Lucy went from being a very popular and fun loving, energetic girl to being unable to walk, dress herself and feed herself. Lucy now receives her food and medication through a G-tube. Without the G-tube we would have lost Lucy a long time ago. But no matter how frail and tired this disease has made her, Lucy still to this day smiles as bright and as big as she did prior to being diagnosed.

Lafora has devastated our lives, but day in and day out we all strive to infuse as much love and affection as we can into Lucy’s life. And our main priority is to keep Lucy as comfortable and as happy as possible.

– Provided by Lucy Terceira’s Sister, Jennifer Terceira

Kristen was a beautiful, articulate, high-achieving, 14 year old, full of fun and curiosity, when she began to experience occasional uncontrollable jerks, which we came to learn soon after, represented myoclonus. The early manifestations were subtle, such as accidentally spilling her milk at the dinner table and breaking dishes when she unloaded the dishwasher. We were seen by a neurologist, who sent her for an EEG and diagnosed Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME). We were told that this is a quite benign type of epilepsy that is readily responsive to antiepileptic medications, usually quite easy to fully control. So she was started on Depakote, and for a few months, went on with the life of a basically normal eighth grader. She announced that she wasn’t going to let her epilepsy be a “big deal” in her life, and her greatest concern was that she was no longer allowed to take baths in the tub. However, we soon began to notice increasing clumsiness, and she began to have difficulty for the first time in her life in honors math. And rather than getting the myoclonus under control with Depakote, she began to have full tonic-clonic seizures and much difficulty walking as well. This was in the winter/spring of 2000.

Kristen was a beautiful, articulate, high-achieving, 14 year old, full of fun and curiosity, when she began to experience occasional uncontrollable jerks, which we came to learn soon after, represented myoclonus. The early manifestations were subtle, such as accidentally spilling her milk at the dinner table and breaking dishes when she unloaded the dishwasher. We were seen by a neurologist, who sent her for an EEG and diagnosed Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME). We were told that this is a quite benign type of epilepsy that is readily responsive to antiepileptic medications, usually quite easy to fully control. So she was started on Depakote, and for a few months, went on with the life of a basically normal eighth grader. She announced that she wasn’t going to let her epilepsy be a “big deal” in her life, and her greatest concern was that she was no longer allowed to take baths in the tub. However, we soon began to notice increasing clumsiness, and she began to have difficulty for the first time in her life in honors math. And rather than getting the myoclonus under control with Depakote, she began to have full tonic-clonic seizures and much difficulty walking as well. This was in the winter/spring of 2000. That’s when I got on the internet and started learning about all the terrible forms of PME. I couldn’t let myself believe that it could be any of those horrible things, and our neurologist was still hopeful that it was simply a matter of not being on the right medication. On the neurologist’s advice, she was admitted to Children’s hospital for a “rapid crossover” of medication, i.e. switching her from depakote to keppra over the course of 3 days rather than the conventional gradual weaning off one medication while slowly increasing the other. (No one I have ever spoken to has ever heard of this kind of unconventional approach.) This turned out to be a disastrous plan, landing Kristen in the ICU in a pentobarb-induced coma. At that point we were told that we may never be able to stop the seizures and that her survival was in eminent jeopardy. I can tell you that only a parent who has endured this experience, watching their child’s flat-line EEG while the body is being kept alive by a ventilator, can understand that depth of suffering.

That’s when I got on the internet and started learning about all the terrible forms of PME. I couldn’t let myself believe that it could be any of those horrible things, and our neurologist was still hopeful that it was simply a matter of not being on the right medication. On the neurologist’s advice, she was admitted to Children’s hospital for a “rapid crossover” of medication, i.e. switching her from depakote to keppra over the course of 3 days rather than the conventional gradual weaning off one medication while slowly increasing the other. (No one I have ever spoken to has ever heard of this kind of unconventional approach.) This turned out to be a disastrous plan, landing Kristen in the ICU in a pentobarb-induced coma. At that point we were told that we may never be able to stop the seizures and that her survival was in eminent jeopardy. I can tell you that only a parent who has endured this experience, watching their child’s flat-line EEG while the body is being kept alive by a ventilator, can understand that depth of suffering. The doctors were able to wean Kristen off the pentobarbitol and on to phenobarbitol so that she no longer required a ventilator and could be transferred out of the ICU. However for 5 weeks after that she never regained consciousness, and we began to make plans to take her home and care for her in a vegetative state. Then one day she woke up.

The doctors were able to wean Kristen off the pentobarbitol and on to phenobarbitol so that she no longer required a ventilator and could be transferred out of the ICU. However for 5 weeks after that she never regained consciousness, and we began to make plans to take her home and care for her in a vegetative state. Then one day she woke up. Only a parent who has experienced this with their child, can possibly understand the depth of that joy. After several days she began to say a few words. She surprised the neurologist who made rounds every day and always held up his pen and other objects for her to name. When she actually named them one day, he was so excited he started jumping up and down and squealing, with tears streaming down his face. After he left the room, Kristen said to me drolly, “He’s a real nut.” Soon she was saying things like: “These pajamas are atrocious”, noticing for the first time the cute frog pajamas I’d dressed her in while she was in her coma. With physical therapy, she regained the strength to walk with assistance. Though she had walked in to the hospital on her own, when she left 5 months later, the ataxia was too severe. She never walked again without assistance.

Only a parent who has experienced this with their child, can possibly understand the depth of that joy. After several days she began to say a few words. She surprised the neurologist who made rounds every day and always held up his pen and other objects for her to name. When she actually named them one day, he was so excited he started jumping up and down and squealing, with tears streaming down his face. After he left the room, Kristen said to me drolly, “He’s a real nut.” Soon she was saying things like: “These pajamas are atrocious”, noticing for the first time the cute frog pajamas I’d dressed her in while she was in her coma. With physical therapy, she regained the strength to walk with assistance. Though she had walked in to the hospital on her own, when she left 5 months later, the ataxia was too severe. She never walked again without assistance. After that nightmare 5 months in the hospital, where her disease progressed so rapidly (no doubt greatly accelerated by the unfortunate “drug crossover” attempt), her progression has been very slow. She was never able to read after leaving the hospital, although, with great effort, she was able to write the alphabet and tried to write some poetry, which she had loved to do before. Her speech was very slow, but, with effort, she could produce whole sentences. She could feed herself with adaptive utensils. She could dress herself with moderate assistance, although it would take over an hour. She didn’t know she couldn’t walk without assistance, so during this early period, there were many falls and trips to the emergency room for stitches. If you turned your back on her for an instant, she’s stand up and over she’d topple. We had a device under her mattress that alerted us when she started to climb out of bed at night. There was very little sleep, even in those days.

After that nightmare 5 months in the hospital, where her disease progressed so rapidly (no doubt greatly accelerated by the unfortunate “drug crossover” attempt), her progression has been very slow. She was never able to read after leaving the hospital, although, with great effort, she was able to write the alphabet and tried to write some poetry, which she had loved to do before. Her speech was very slow, but, with effort, she could produce whole sentences. She could feed herself with adaptive utensils. She could dress herself with moderate assistance, although it would take over an hour. She didn’t know she couldn’t walk without assistance, so during this early period, there were many falls and trips to the emergency room for stitches. If you turned your back on her for an instant, she’s stand up and over she’d topple. We had a device under her mattress that alerted us when she started to climb out of bed at night. There was very little sleep, even in those days.

The migraine headaches began when she was 12, periodically leading to tunnel vision and short blackouts. When she was 13 Kelsey began to suffer a migraine during a basketball game and quickly became completely unresponsive. She was awake and her eyes open, but she was almost catatonic, not responsive to any external stimulation. At the hospital she did not react to my presence, did not turn her head or move her eyes. Only when they performed a spinal puncture to test for meningitis did she let out a scream. I was overjoyed that she had “snapped out of it”. A few minutes later I witnessed the seizure. Only because I had suffered from epilepsy as a teen did I recognize the small shaking to be a seizure. The doctor immediately gave her an anti-convulsion drug and we were directed to a neurologist and Kelsey began taking daily medication to control the seizures. Still, we were hopeful. Certainly as my epilepsy passed, Kelsey’s would as well. Along with the medication came the modest drop in her grades. She had always been a perfect or near perfect student. However when her grades began to slip, I presumed this was due to the medications. For a bit over a year she seemed to be moving along okay. At age 14 and with two older siblings, her thoughts moved to driving. Indeed when she was 15 and had another seizure after nearly two years of being seizure free, she cried, realizing that this reset the calendar and that she was again two years away from being able to drive. By this time she was still a very good student, but not the nearly perfect student she had once been. This began our journey through what another parent has aptly described as “prescription elimination”. And the difficulties intensified. In the 10th grade she suffered more seizures, often on the soccer field where she was the goalie on her high school team.

The migraine headaches began when she was 12, periodically leading to tunnel vision and short blackouts. When she was 13 Kelsey began to suffer a migraine during a basketball game and quickly became completely unresponsive. She was awake and her eyes open, but she was almost catatonic, not responsive to any external stimulation. At the hospital she did not react to my presence, did not turn her head or move her eyes. Only when they performed a spinal puncture to test for meningitis did she let out a scream. I was overjoyed that she had “snapped out of it”. A few minutes later I witnessed the seizure. Only because I had suffered from epilepsy as a teen did I recognize the small shaking to be a seizure. The doctor immediately gave her an anti-convulsion drug and we were directed to a neurologist and Kelsey began taking daily medication to control the seizures. Still, we were hopeful. Certainly as my epilepsy passed, Kelsey’s would as well. Along with the medication came the modest drop in her grades. She had always been a perfect or near perfect student. However when her grades began to slip, I presumed this was due to the medications. For a bit over a year she seemed to be moving along okay. At age 14 and with two older siblings, her thoughts moved to driving. Indeed when she was 15 and had another seizure after nearly two years of being seizure free, she cried, realizing that this reset the calendar and that she was again two years away from being able to drive. By this time she was still a very good student, but not the nearly perfect student she had once been. This began our journey through what another parent has aptly described as “prescription elimination”. And the difficulties intensified. In the 10th grade she suffered more seizures, often on the soccer field where she was the goalie on her high school team. Early in 2012 she was admitted to Children’s Hospital of Orange County (CHOC) for week long epilepsy monitoring. By this time she was 16, with a reasonably normal high school experience, goalie on the school soccer team, going to football games and dances. But her seizures were more and more frequent and her grades continued to fall. Still, we anticipated that she would outgrow the seizures and that once she was off her medications her grades would return to normal. This, after all had been precisely my experience. But her physicians indicated that the monitoring showed such widespread activity that they did not expect her seizures to end, that she would be on medication her entire life. This was the first heartbreak. Unfortunately, even with changes in her medication, the seizures continued. So too did the hospital stays. Over the six months from April through September, Kelsey spent over two months in the hospital with her physicians running all manner of tests to better understand what was happening.

Early in 2012 she was admitted to Children’s Hospital of Orange County (CHOC) for week long epilepsy monitoring. By this time she was 16, with a reasonably normal high school experience, goalie on the school soccer team, going to football games and dances. But her seizures were more and more frequent and her grades continued to fall. Still, we anticipated that she would outgrow the seizures and that once she was off her medications her grades would return to normal. This, after all had been precisely my experience. But her physicians indicated that the monitoring showed such widespread activity that they did not expect her seizures to end, that she would be on medication her entire life. This was the first heartbreak. Unfortunately, even with changes in her medication, the seizures continued. So too did the hospital stays. Over the six months from April through September, Kelsey spent over two months in the hospital with her physicians running all manner of tests to better understand what was happening. All we can hope for is a miracle development that will give her back that which is being taken. All we can hope for is a miracle development that will give us back our daughter.

All we can hope for is a miracle development that will give her back that which is being taken. All we can hope for is a miracle development that will give us back our daughter.